Slobodan Dan Paich Comparative Culture Papers

Presented 20-23 of March 2008 in Athens at the International Conference on Mediterranean Studies for the Athens Institute For Education And Research. www.atiner.gr

Transmigration of Music

The Significance of Itinerant Musicians in Mediterranean Cultures

Slobodan Dan Paich

Director and Principal Researcher

Artship Foundation, San Francisco, USA

Abstract

Troubadours are the paper's central example. Broader issues of social currents in Mediterranean cultures will be touched upon through looking at Troubadours and, by reflection, Trouveres, as well as other itinerant musicians' collaborations with Alfonso X, The Wise, emperor-musician. The paper will touch upon possible influences on Troubadours and Trouveres by the Albigensian culture of southern France, as well as Arab, Sephardic, and Gypsy music confluences. As a sub-theme, other strands of music will be discussed. All of the examples will be presented as part of the history of ideas & as social, societal manifestations—exploring ideas of cultural continuity and adaptation. Technical, musical, or musicological issues will be dealt with only to illuminate the central narrative. Observations and invitations to discuss further the interconnectedness and diversity of Mediterranean cultures will follow two interweaving strands: first, the role of the professional itinerant musicians; and second, the displacement and resettlement of people throughout Mediterranean history.

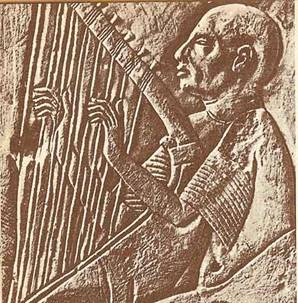

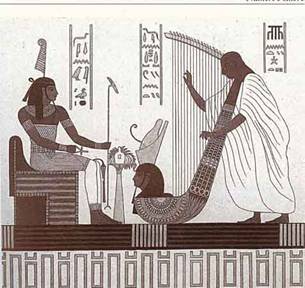

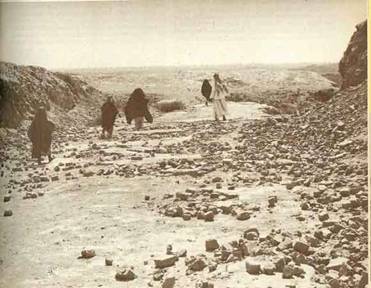

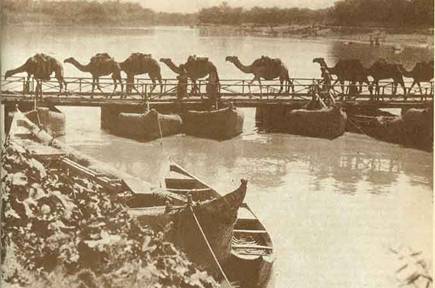

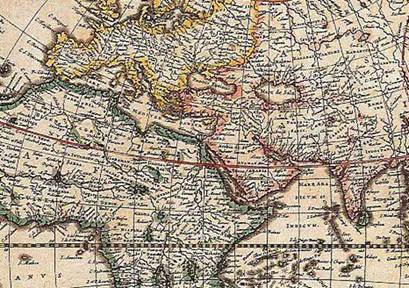

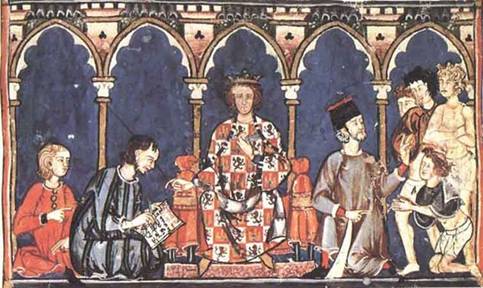

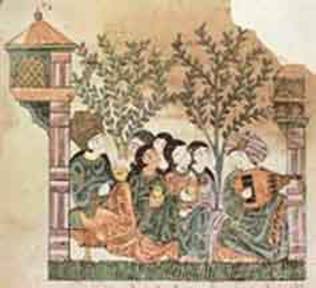

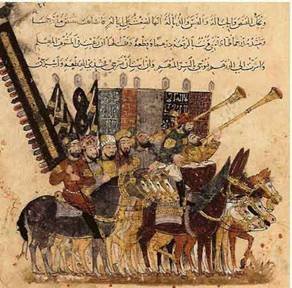

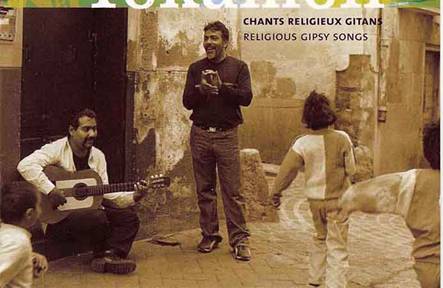

[The Illustrations in this paper provide a context for the reading of images, collected from a broader research into the history of ideas carried out by the Artship Foundation. We will add specific captions and, potentially, other images, after completing the current research and evaluating these visual and documentary source materials related to our topic of itinerant musicians.

Opening Thoughts

To approach the vast subject of music's impact on Mediterranean cultures without making generalizations, this paper will focus on the significance of itinerant musicians, starting with the phenomenon of the wandering Troubadours.

Transmigration: the Title's Invocation

Transmigration is loosely used here to signify the transmission of an elusive musical essence, from musician to musician and from place to place. The term transmigration is part of the ancient Greek concept of metempsychosis, the 'transmigration of souls,' associated with the philosophers Pythagoras, Plato, and later Neo-Platonist—and possibly Orphic—lore and folklore. Plato's notion of innate knowledge is somewhat associated with metempsychosis. However, we leave the issue of transmigration of the soul for other researchers to examine; we present no opinion about that phenomenon as it is outside our expertise. We use it to signify a poetic transmission from living person to a living person.

Migrations of a Single Song

The Provencal Carnival song Adieu Pauvre Carnaval reappears as the Mozarabic Easter hymn in Lebanon known as Wa Habibi. One of the most moving recordings of Wa Habibi is by a Tunisian singer, Lamia Bedioui, collaborating with Greek singer, Savina Yannatou, on the album Terra Nostra, accompanied by the ensemble Primavera en Salonico (ECM 2001). This haunting melody appears also in Le Fougere by the Neapolitan composer Giovanni Pergolesi (1710-1736). The first work to establish Pergolesi's reputation was his sacred drama, La Conservatione di San Guglieme d'Aquitania (1731), 'given its first performance by his fellow students at a Naples monastery' (Goldberg, early-music portal, 2008). Guglieme d'Aquitania, or Guillaume IX of Aquitaine (1086-1126), is recognized as the first Troubadour of Provance.

Troubadours and Trouveres, a Summary

The inception, early development, and evolution of the literature of idealized noble love does not have a significant surviving record. One thing, however, appears to be certain: that Troubadours were artists from diverse social backgrounds, and to be a Troubadour, one needed only two qualifications: that one created and lived in the mode of courtly love, and that one was familiar and at ease with the culture of courtly ideals.

The majority of 19th century historians have traced the origins of movements or events to a single person, and little time has been given to the study of sub-cultures, trade patterns and movements, or any other societal phenomena. The cultural climate for understanding the Troubadours' inception, and their later influence is, and may remain, a field for open questions and contrasting hypotheses.

Guillaume IX of Aquitaine, who, as mentioned before, was the first recorded Troubadour, used the Romance vernacular Occitan or Provencal for his poems. His titles, which point to a definite geography and place, are inseparable from Troubadour territory: he was the Duke of Aquitaine and Gascony and the Count of Poitou. His Occitan title was Guilhèm de Peitieus. He also was one of the leaders of the Crusade of 1101.

All the above details about Guillaume IX of Aquitaine bring us into a definite place and time of early Troubadour activity: to the end of the 11th and the beginning of the 12th centuries in and around Poitiers, in the linguistic territory of Occitan, in what is today southwestern France.

Zdravko Batzarov on the Orbis Latinus website dedicates a page to the Occitan or Languedoc language and territory. He also articulates the Latin origin of langue d'oc and langue d'oil, the main linguistic distinction between Troubadours and Trouveres:

Occitan language (also called Proven & al or Languedoc) is a Romance language… The name Occitan is derived from the geographical name Occitania, which is itself patterned after Aquitania and the characteristic word oc… The name Languedoc comes from the term langue d'oc, which denoted a language using oc for yes (from Latin hoc), in contrast to the French language, the langue d'oïl, which used oïl (modern oui) for yes (from Latin hoc ille). Languedoc refers to a linguistic and political-geographical region of the southern Massif Central in France.

Territories and Itinerant Musicians

One of the most obvious issues for itinerant musicians is their need to traverse territories. A healthy person can walk about fifty kilometers on a long summer day from sunrise to sunset. The traditional sense of one's country of origin was such a full day's walk. For an itinerant musician, traversing a territory in one day must have presented major problems. How safe was the territory? What were the landmarks, road signs and resting spots? Where would drinking water be found? Other things also determined a journey. Were the musicians invited? Did they carry a letter of introduction? Would they go to a castle of a baron on spec?

It was always safer to travel in numbers along trade and pilgrim routes. Often one had no choice but to pay a road fee to a baron so his solders would protect a group of travelers against bandits. For a musician, protecting his instrument and his court finery must have been a major logistical issue. Aristocratic and successful Troubadours must have traveled on horses.

Troubadours such as professional jongleurs, with families moving around with them, must have traveled in wagons. The living models that may help us understand the itinerant musicians of the Middle Ages are the gypsies (or Roma people, a usage preferred by a number of writers in some countries) who, to this day, have similar issues to face and who have been using cars only for the last twenty years. They are famed for their musical abilities, readiness to perform for hire, and their knowledge of roads and horses.

Trade Routes

If silk can travel from China, be spun or woven in Damascus as a brocade or damask, and then reach the courts of Languedoc, Galicia, Granada, or Fez, how difficult would it be for an idea, song, or musical instrument to go back and forth along the same routes?

Discoveries of prehistoric cutting tools point to a vast network of trade routes that were active very early in human history. These networks may be as impressive as Stonehenge. Here is another example of prehistoric trading:

Oxygen isotope analyses of Spondylus shells from Neolithic sites suggest that the source for the shells used as ornaments in the Balkans and central Europe during the fourth millennium BC was the Aegean and not the Black Sea. The trade in Spondylus may have taken the form of an exchange of gifts. (Shackleton & Renfrew, 1970)

There is an overwhelming amount of evidence from material culture of the existence of established maritime and overland trade routes and their extensions throughout Europe. These international trade routes persisted through many civilizations and cultural periods.

Neighboring Watersheds

Lunde (2005) writes about the Venetian codependence on Arab maritime power in the Middle Ages that had grown out of the Arab merchants' precise understanding of the monsoon patterns in the Indian Ocean watershed. He also analyzes the origins of the word monsoon, which sheds light on the importance and cosmopolitan influence of Arab maritime power prior to European sea exploration. He further describes how the regular sailing of the Venetian convoys, the mude, were synchronized with the Indian Ocean monsoon trade winds:

The economies of northern Europe were similarly linked—indirectly, like a train of interlocking gears—to the Indian Ocean monsoon: From Venice, after the return of the mude, spices and textiles traveled overland and by internal waterways to the trade fairs of northern Europe. (Another set of gears driven by the monsoon linked the Indian Ocean economies with China) (Lunde, 2005).

The Venetian trade monopoly in the Mediterranean was established after the Venetians led the 1204 crusade against Constantinople, and secured treaties with the Mamluk Sultan (Lunde, 2005).

While merchants such as the Venetians developed their trades, they set a primary value on gold. In contrast, the aristocrats' power was derived from land; for musicians, teachers, court advisers, and other itinerant experts, their currency was their skills. Sometimes, those skills could outweigh any amount of gold, and gain them entrance and employment at the inspiring and vital courts of Aquitaine, Galicia, or Damascus. Lunde continues:

In the Islamic world, gold was a tool. Mocenigo's equation, in which fear and respect could be had for gold, would have sounded blasphemous to Muslims, for whom it is God alone who commands fear and respect. Muslims believed that gold and silver must circulate, and this circulation, called rawaj, was a social and religious duty (Lunde, 2005).

The symbiosis of medieval maritime trade must have had an effect on phenomena such as the Troubadours and other itinerant culture-workers. All of these transactions had to be communicated with a shared language for international communication and expression, a lingua franca.

Lingua Franca

Occitan was the lingua franca, the shared international language, of the Troubadours. In some ways it is closer to Galician and Portuguese than to French as we know it today. (That may be one of the reasons why the patron and protector of Troubadours and musicians, the neighboring Spanish king, Alfonso X, favored Galician as a language of poetry in his Spanish territories.) And of course, as mentioned before, Guillaume d'Aquitaine, the recognized proto-Troubadour, wrote in Occitan.

One of the best-known Italian Troubadours was San Francis of Assisi, whose father—a cultured and well-connected merchant of linen—called him Francis after the Francs, whose culture, refinement, and courtly values he must have adored.

Originally "Lingua Franca" (also known as Sabir) referred to a mix of mostly [Latin] Italian with a broad vocabulary drawn from Persian, French, Greek and Arabic. Lingua Franca literally means ‘Frankish language.’ This originated from the Arabic custom of referring to all Europeans as Franks (Batzarov, 2000).

Mastery

Who were Guillaume's, tutors, mentors, living and historic models, and references? What kind of cultural sensitivities and grooming was he was exposed to? We might ask the same questions about Alfonzo X, the Wise. Another decisive question: What level of mastery in physical combat skills, military strategy, diplomacy, and art did the patrons of the itinerant musicians attain, and to what extent did these patrons depend on the experts at their courts? The Oriental and Occidental world in classical, Medieval, and Renaissance times abounded with itinerant court advisers, musicians, and skilled or learned people.

One characteristic of complete performance mastery is the integration of virtuosity and emotional communication, recognizable as an inexplicable visceral response by the listeners. The piece is not just interpreted—it comes to life in front of their eyes and in their cognitive being. Levitin (2006) writes of mastery in his book, This Is Your Brain On Music, in the chapter titled, What Makes a Musician?:

…Ten thousand hours of practice is required to achieve the level of mastery associated with being a world-class expert—in anything. In study after study, of composers, basketball players, fiction writers, ice skaters, concert pianists, chess players, master criminals, and what have you, this number comes up again and again. Ten thousand hours is roughly equivalent to three hours a day, or twenty hours a week, of practice over ten years. Of course, this doesn't address why some people don't seem to get anywhere when they practice, and why some people get more out of their practice sessions than others. But no one has yet found a case in which true world-class expertise was accomplished in less time. It seems that it takes the brain this long to assimilate all that it needs to know to achieve true mastery.

Levitin opens to us an appreciation and understanding of the expertise accomplished musicians have, and why a good one would have been rare, and in demand.

This also raises new questions: first, did the aristocratic Troubadours themselves achieve a mastery of their art by investing years of time and practice into their music? Or perhaps they surrounded themselves with itinerant and resident musicians who devoted much of their lives to rigorous practice. Perhaps the princes wrote what other musicians sang. This may be the reason why the poetry has survived, but not much of the music has. Did each itinerant musician sing the verses or accompany the poets differently?

Troubadour Output, Parallels, and Possible Sources

Fin d'amour, courtly love as a cultural phenomenon, brought fresh elements into the social sensibilities of the feudal Christian world of medieval Western Europe. It provided the ecclesiastically dominated culture of Europe with a poetic language for the experiences of love, both secular and sacred.

The Troubadour's attitude became a significant factor in the augmented social role of women (Bogin, 1980). It gave women an image of themselves—although uncomfortably idealized at times—and changed the role they played in the male imagination. This shift was from a ‘sinful’ Eve to a Madona Inteligencia, as described by the late Troubadour movement of Dante's time, the Fedeli d'Amore.

Male bonding and the idealized woman

The fact that anyone could come from anywhere and besiege your castle or town and claim your territory was an unsettling reality of the middle ages. Brute force had to be met with brute force. Military readiness was an imperative for survival. To use a cliché for the moment, it seems that the male psyche loves the heroics of war. Apart from physical fitness and martial skills, the male bonding of soldiers is a significant characteristic—an atavistic quality—that war, hunting, and navigation bring about. Karen Blixen, a Danish writer, wrote that her uncle, a general, was both in love with his wife (as an individual, Eros) and with his regiment (as a group, bonding).

It may be interesting to study the relationship of the two dynamics—idealizing women and the bonding of knights and soldiers—as a possible interdependent cultural loop: an expression of ardor for Her sake among the cohort of combatants.

One woman such as Eleanor of Aquitaine (Markale 2007) could champion many knights simply by paying them some small attention—no more than exchanging a meaningful glance, or attentively watching their jousting display from the safe distance of her court. With their imaginations aflame, they would valiantly fight side by side in some later battle, next to their equally infatuated comrades. If you were not a poet, philosopher, or a musician, the outlet for such passion—awakened by an unattainable Lady—was expressed in the jousting games and in battle. Was not the original Troubadour, Guillaume IX of Aquitaine, also one of the leaders of the first Crusade?

The significant point of the Troubadours' contribution was the celebration of the personal experience reflected in the direct knowledge of love—both of the male Troubadour for his chosen lady, and of the Occitan women Troubadours, the Trobairitz, who sang about their champions.

Observing the Troubadours' virtuoso writing and passion for the direct knowledge of a loved one leads us to some parallel ideas. The temptation to jump straight into a Gnostic connection is great, but we shall hold off from making any definite conclusions.

Sophia

Perhaps the most haunting figure in the Gnostic cosmology, Sophia is seen variously as the personification of divine wisdom, as a female divinity equated with the Holy Spirit, as an allegory of the soul separated from its true home, and as the inspiration for every old story of a ‘damsel in distress’ (Clifton, 1998).

The ambiguity of direct experience and knowledge of ‘I and Thou’ versus an institutional sacrament, needing an ecclesiastical body, is probably one of the reasons later Troubadours were suspected to be partners and accomplices to the Cathars. As mentioned earlier, the last recorded Troubadours, the Fedeli d'Amore, had a Sophia of their own: their Madona Inteligencia. Was it that their aspiration for a direct relationship with their Sophia that made them form a secret society to avoid the eyes of the Inquisition? The direct experience of Sophia, as the feminine ideal, may explain why it was not too difficult for some of the poet-musicians—such as Alfonzo X and his circle—to replace the Troubadours' lady with the Virgin Mary.

We are always thankful to Arab scholars and intellectuals of the Middle Ages for keeping that connection to Greek philosophy as a continued thread. MacLennan (2001) writes in his An Interpretation of Courtly Love, summarizing Plotinus's Neo-Platonic discourse about mind:

From this perspective the Nous, the Intellectual/Spiritual Principle, emanates from the One, but is directed back toward it, in an eternal cyclic living flow, by love (eros) of the Good (which is the One). In Neoplatonic philosophy the Nous (Mind) is seen as feminine and is identified with Wisdom (Sophia, Sapientia), Philosophy, Angel of Knowledge, Lady of Thought, etc. (More precisely, each level is ‘feminine,’ i.e. receptive, with respect to the level above it, and ‘masculine,’ i.e. active, with respect to that below.) In Christian Neoplatonism, Nous is often identified with the Holy Spirit (traditionally feminine) or with the Virgin Mary (in which case the One is identified with the Trinity). Henceforth I will call the Nous ‘Wisdom’ and use the feminine pronoun (MacLennan, 2001). [our emphasis]

On the subject of Wisdom as feminine, Clifton (1998), in his Encyclopedia of Heresies and Heretics, writes:

Greek-speaking Jews of the Roman Empire translated the Hebrew word for "divine wisdom,&quo; Hokhmah, as ‘Sophia.’ (Both words are grammatically feminine in their respective tongues.) Although fundamentally monotheistic, some Jews, particularly those living in Alexandria and other areas away from Palestine and removed from the temple of Judaism, developed what is called the ‘Wisdom Literature,’ a group of scriptures portraying Wisdom personified (Clifton, 1998).

Clifton ends his essay with:

The Wisdom of Solomon states, ‘Wisdom is radiant and unfading, and she is easily discerned by those who love her, and is found by those who seek her’ (Clifton, 1998).

Ibn Hazm

There is a book that has always created discussion among Troubadour scholars: Ibn Hazm's Tawq al-hamama, The Ring of the Dove. This work is sometimes called The Dove's Neck Ring. Ibn Hazm (994-1064), who primarily wrote about law and theology, wrote about love in an attempt to compose in an Arab-Persian mode of elegant writing.

Arberry (1953), translator of The Ring of the Dove, in his description of the childhood and upbringing of Ibn Hazm, writes that Hazm '...enjoyed a happy though secluded childhood, and the advantages of an excellent education; he tells us that most of his early teachers were women.' This tiny glimpse into Andalusia's aristocratic practices of upbringing may offer an imaginative leap of thinking about possible positions of learned and highly educated women as early childhood teachers and mentors of future lords. In some Islamic households, young boys are allowed into the confines of the women's quarters, and nurtured there.

The impact of women who were philosophers, musicians, theologians, and storytellers, and who also happened to teach, cannot be underestimated. Scheherazade and Hypatia of Alexandria, are two examples. Hypatia (c.360-415), a Hellenized Egyptian, was a mathematician and the head of the Platonic academy at the Serapeum in Alexandria. She is credited for the invention, or significant improvement of, the astrolabe, an instrument important in Arab navigation. Although almost forgotten by history, she is a great model for imagining the early childhood teachers of aristocrats in Andalusia and possibly Occitan. The impact of such women gives us a hint of a feminine figure like the benevolent Sophia, nurturing the young minds of future poets of either the elegant literature of the Arab aristocrats and intellectuals, or of the Occitan Troubadours.

In his summary of Persian and Greek influences on Arab culture, Arberry writes:

The Persians introduced them [Arabs] to the idea of adab, a term most difficult to translate; broadly speaking, adab is a form of prose composition whose primary purpose is not religious but secular, and which is intended not merely for instruction but also for enjoyment. It was the Persians who taught the Arabs to appreciate and to write elegant prose... and encouraged them to amorous adventures. From the Greeks the Arabs learned science and philosophy, the art and the delight of discussion and dialectic (Arberry, 1953).

Here he helps us see how, organically, Greek thought lived in Arab and Andalusian writings. Also noteworthy is his observation that poets were the heroes of the numerous desert romances.

Leaman and Albdour (1998) write of how The Dove's Neck Ring deals with the concept of love:

In it he [Ibn Hazm] analyses the concept and differentiates between divine love, which is placed at the highest level, and affection, which is the lowest. Clearly influenced by Plato's Phaedrus and Symposium, he regards love as the coming together of otherwise incomplete beings (Leaman & Albdour 1998).

As we follow the influences crisscrossing the Mediterranean in time and geography, it becomes clear that Occitan culture was in some way an exception, a precedent in the Christian European world, just as Andalusia was in the Muslim world.

Hazm's life was such as precedent. He was born into an Andalusian aristocratic family, loyal to the Umayyad dynasty as it was declining. He had a stormy political career, was imprisoned three times, and banished from Cordoba on several occasions. In 1027 he was in Jativa, probably incarcerated, where he composed The Dove's Neck Ring (Arberry, 1953). He tried to stay away from politics for the rest of his life. ‘…But he by no means kept clear of trouble, for his religious views were in conflict with the prevalent orthodoxy and his writings were publicly burnt in Seville during his lifetime’ (Arberry, 1953)

Approximately two centuries later, the Occitan and Provencal Troubadour phenomena suffered at the hands of inquisition during the Albigensian Crusade against the Gnostic Cathars (1209- 1229).

The Albigensian Connection

It is an interesting fact that the territories and geography of the Troubadours and their patrons is very close to most territories of the Albigensian heresy. The Albigensians were a dualist sect that flourished in southern France in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, though they may have been part of an international movement. They were also called Cathars (from Greek katharos, "pure"). The Aristotelian concept of catharsis”the effect of a performance upon spectators”is derived from the same word. The Greek etymology possibly points to the connection of the Cathars with the Byzantine empire: they may have been connected to the Paulicans, who lived on the border between the Byzantine empire and the Arab world (Armenia or Cappadocia), or with Islamic Persia or other states on the Black Sea, or the Bogomils of the Balkans (Bulgaria or Bosnia) at the western borders of the Byzantine Empire, bordering the Catholic sphere of interest.

All three—Paulicians, Bogomils, and Cathars—lived on the borders between Christian and Islamic nations. Paulicians and Bogomils were often used as border guards by the Byzantine Emperors. At times they fought against, and at others flowed with, Islam and the Arab world. During times of persecution, initiated from either Constantinople or Rome, some of them adopted Islam without great difficulty”particularly the Bogomils of Bosnia and some Paulicians of the upper Euphrates river. This may be due to the creed of Islam (paraphrased here by an outsider, attempting to elicit an understanding of the general ideas): there is no other god but the One and that Mohamed was his prophet. This may have been easier to adopt, as no carnal human worship is implied in Islam. Islam may not have been contradictory to their dualist beliefs and may also have offered a safety from persecution. Although not free from strife and the military campaigns of feudal society”nor from the literalness of religious belief”the plurality, multi-ethnicity, and sophistication of the medieval Muslim world could absorb them.

The Albigensian Crusade was a catalyst in the creation and institutionalization of the medieval Inquisition as well as the Dominican Order. As we mentioned earlier, itinerant musicians had to navigate all of the wars nobles waged over land and dominion, and had to survive through ideological zones of favored or persecuted beliefs. It seems that whoever is in power creates their own ideological cleansing devices, and the culture workers have to navigate through them.

Alfonzo X, el Sabio, “The Wise,” and the Music

One of the most comprehensive manuscripts on medieval music, The Cantigas de Santa Maria, was commissioned, and possibly partly composed by, Alfonso X (1221-1284). Petersen (2006) the web page: A list of the works commissioned by Alfonso X beautifully articulates the collaborative quality of many experts involved in the creation of the manuscript:

A large staff of by and large anonymous musicians, scribes, calligraphers and artists was employed to compile and illustrate the manuscripts, inscribe the captions that explain the scenes depicted in the individual panels, and provide the musical accompaniment and its notation. Each facet of the multimedia opus was a collaborative undertaking. Alfonso, who considered himself a "trovador," seems to have taken immense pride in his musical ability. It is thought that as well as being placed on display, the Cantigas were likely performed, thus reaching a wider audience.

Alfonso X's song cycle cannot be overestimated as a unique and beautiful codex which is both a treasury of poetics in Galician and a piece of nonverbal, documentary material evidence of medieval music culture. The codex's illustrations show Arab, Jewish, and Christian musicians performing together on a remarkable variety of instruments. It is a celebration of diversity, vitality, and mastery of professional”and probably itinerant”musicians. Petersen (2007), also beautifully describes the musical qualities of the manuscript:

A corpus of considerable artistic unity, the 430 miracles are interspersed at regular intervals with short lyrics in praise of the Virgin. Of the wide variety of verse forms used, the "z&ecaute;jel" predominates. The melodies derive from both sacred (western chant, mozarabic liturgical music) and popular music, although there is a large group said to have no relation to chant whatsoever and that can't be analyzed according to the western modal system. This variety would seem to be attested to in the illuminations themselves. One codex depicts seventy-odd musicians, Christian and Moslem, playing a variety of instruments of all types (wind, string, percussion, etc.). Much debate revolves around the debt to Arabic models and melodies (Petersen, 2007).

We do not have room in this paper to analyze and reflect upon the remarkable translations from Arabic into Castilian Spanish that Alfonso X commissioned, nor on the creation of new material he encouraged. These manuscripts were works of encyclopedic interest, and their subjects ranged from treatises on science, medicine, mathematics, philosophy, and astronomy, to the books on law, courtly upbringing, etiquette, games, and music. As a lawgiver, he wisely adopted the vernacular Castilian as a seed of Iberian national identity but kept Galician as the language of poetry and song. He sheltered many intercultural refugees from the Albigensian Crusade, who added to his encyclopedic and cosmopolitan court.

Menocal (2002), in her book Ornament of the World, describes particular migration patterns that led away from the site of the Albigensian Crusade, traversed by Jewish thinkers and other practitioners of non-traditional belief systems. Their flight may give us a sense of what the itinerant musicians of that geography and time had to go through:

A rich mystical tradition thrived among the communities of Jews who lived on either side of the Pyrenees and who shared the vernacular often referred to as Provencal. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, this land, with its intimate ties to the still-Arabized Christian courts of Catalonia and Aragon, had been the breathing ground of a whole stable of institutional misfits. This was the native land of the first generation of poets who attempted to replace Latin as a literary language with the vernacular that within a few years would be poetically dubbed langue d'oc, “the language of yes.”

Young Alfonso X, by associating with and sheltering this type of intellectual and artist, was, unknowingly, alienating his court from the mainstream of the Roman Church. Menocal helps articulate the relationship of Jewish Kabbalists to the Albigensians:

It [the Occitan territory] was also the seat of the Jewish mystics and esotericists we call kabbalist. Culturally they were much like their Andalusian brethren, but spiritually they were at odds with the Andalusians' intellectual and philosophical visions of faith. This “land of yes” seemed to specialize in nay-saying, and it was also the breeding ground of the Cathar, or Albigensian, heresy, the resolutely Manichean “Church of the Purified” that Rome began to come down on heavily by the mid-twelfth century.

As he was doing with the church, Alfonso X was also possibly alienating himself from established Jewish institutions flourishing in cities like Toledo, which later turned against him. Menocal continues:

Prominent among those who emigrated to the more congenial atmosphere of Oc-speaking Catalonia, whose vernacular tongue was barely distinguishable from that spoken just to the north of the Pyrenees, were Jews among whom Kabbalah had been cultivated for years, alongside Cathars and troubadours alike. In places like Gerona, a town no more than 120 miles from Cathar strongholds such as Toulouse, and much closer to many smaller towns”all left ravaged in the last years of the Albigensian Crusade.

By comparison (and without having enough historic material at the moment to review possible contrasting theories), we can only openly hypothesize that Alfonso X's association with Arab wandering musicians was not always pleasing to the institutionalized Islamic circles in Iberia either, as they sided with his opponents toward the end of his life. Previously we cited an example of that attitude when writing about the proto-Troubadour Ibn Hazm (994-1064) and his book, The Ring of the Dove. Music, devotional or secular, was not universally favored by all clerics and had a very delicate relationship to established Islam, although some Arab, and later Ottoman, courts encouraged and cultivated a music culture. If not in the courts, then the institution of the caravanserai, the roadside inn, was a place of music making and the exchange of songs.

Directly or indirectly, music, musicians, and music centers may have been Alfonso X's deep connection to the kingdom of Morocco. This may have been the root of his alliance with Abu Yusuf Yakub, the ruling Marinid sultan of Morocco, an alliance which led to Alfonso X's denouncement as an enemy of the faith by the church. Alfonso X, as a musician, may have gravitated towards Morocco as would the fellow Troubadours of the next generation, such as St. Francis of Assisi and Ramon Lull, in their pre-conversion days. Were they looking for, and trying to connect to, a musical tradition and schooling available there, rather than seeking any outwardly religious or ideological movement?

The Iberia of Alfonso X gives us a context to understand the precarious position of individual cultural workers and groups of master performers, and may help us reflect and shed light on itinerancy as a means of preserving cultural identity against spasms of ethnic cleansing.

To contextualize further, in closing this chapter, we shall recapitulate briefly the career of Alfonso X, the Wise. He was the King of Castille, León, and Galicia from 1252 until his death in 1284. He also was elected German King in 1257. He was the eldest son of Ferdinand III of Castille and Elisabeth of Hohenstaufen, a daughter of emperor Philip of Swabia. This gave him claim to the linage of Swabian Kings and led to his becoming the Holy Roman Emperor in 1257.

As the king of the Germans, he presumed to be entitled to the support of the Roman Church. The title of the Holy Roman Emperor triggered his vision of himself as a pan-European ruler, and this ambition took him out of his Iberian wisdom into a political arena beyond his means. As an aristocrat he did not understand the importance of a prosperous middle class and peasantry, and he taxed them ruinously.

So, from the protector of diversity, intellectual freedom, and a patron of the synthesis of Arab, Jewish, and Christian art and thought, Alfonso X inadvertently became one of the early catalysts for ethnic cleansing and religious fanaticism in late medieval and Renaissance Spain. Not only the itinerant musicians, but also whole groups of people”the ones who could not change their tune”had to move on and resettle in another part of the Mediterranean.

Conquest and Exile: Migratory Patterns

The historic dynamics of the Iberian Peninsula are exemplified by the cultural climate and politics of Alfonso X. This land, wedged between Africa and Europe, the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, prospered in the Middle Ages through its connection to the Arab world's understanding of the sailing conditions of the Indian Ocean.

The geo-pulse between the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea was expressed through trade cycles and routes, and gave birth to the refinements of the pre-Inquisition era and culture of early medieval Europe. The more documented geo-pulse that occurred between the Atlantic and Mediterranean during the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery brought about new migratory patterns and resettlements of great numbers of people.

Lunde (2005), whom we quoted in the previous section on Mediterranean trade in the Middle Ages, writes about the 1415 Portuguese capture of Ceuta, on the Moroccan coast opposite Gibraltar. He continues by saying that Ceuta was the port from which the Muslim invasion of Spain had been launched in 711; its capture marked the beginning of the Portuguese push around Africa that culminated in the discovery of the sea route to India:

Azurara, the official chronicler of the capture of Ceuta, painted a glowing picture of the town, which he called “the key to the whole Mediterranean Sea.” The city astonished the Portuguese soldiers, who were amazed at its fine houses, the gold, silver and jewels in the markets and the cosmopolitan population. They saw men “from Ethiopia, Alexandria, Syria, Barbary, Assyria… as well as those from the Orient who lived on the other side of the Euphrates River, and from the Indies.” Azurara clearly states that one of the motives of the expedition was to seize control of the African gold trade: Forty years later, with the establishment of the fortress of São Jorge da Mina on the Guinea coast, 25 to 35 percent of the gold that had formerly made its way across the Sahara to North African markets and to Mamluk Egypt now passed into the hands of the Portuguese instead.

Pearson (2007), in his article "Ceuta and Melilla”Two Spaniards in Africa," writes:

There are two small places in North Africa, within Moroccan boundaries, situated on the northern coast of the Maghreb, on the southern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, Ceuta and Melilla, that to you and me seem like integral geographical parts of the Kingdom of Morocco, when in fact they aren't. They actually belong to Spain. Ceuta and Melilla are two Spanish exclaves in North Africa.

A contemporary musician arriving with a guitar or cora, an instrument resembling a lyre, at the border of those two towns, besieged by immigration requests, may find it more difficult to enter than a troubadour of the Middle Ages who may have gained entry simply by demonstrating his mastery.

Pearson (2007) describes how, after re-conquest of the last bastion of Al-Andaluz”Granada”Spain decided in 1497 that the Port of Melilla in North Africa would be of extreme strategic importance. Melilla was taken in retaliation for the long occupation of Spain. Strategically important, Ceuta had a different history: A Portuguese town from 1415-1580, the Spanish acquired it after Spain's King Felipe II succeeded to the throne of Portugal in 1580. Both cities were free ports before 1986 when Spain joined the European Union. Pearson continues:

The Government of Morocco has called for the integration of Ceuta and Melilla, along with uninhabited islands such as Isla Perejil, into its national territory, making references to Spain's territorial claim to Gibraltar. But the Spanish government, and both Ceuta's and Melilla's autonomous governments and inhabitants, reject such a comparison on the grounds that both, Ceuta and Melilla, are integral parts of the Spanish state.

We include these territorial examples not for reasons of forwarding an opinion of right and wrong about geopolitics, but to point to remnants and contradictions of the very large migratory patterns of displaced peoples. The land, with its chain of displacements, may carry contradictory memories for the different populations that inhabit it. Reflecting on the displacement of people in a paper on the dynamics of musical migrations may help us understand a bit more about the issues of resulting cultural preservation, shifts of values, tensions, and the collective pain that ethnic and political refugees experience and hold.

Thessalonica

The history of Thessalonica in northern Greece is a poignant example of shifts of population. Stefanos (2004), in his web article Thessaloniki, talks about the city's survival. After giving the list of invaders, such as Crusaders, Normans, Saracens, Slavs, Avars, Catalans, he writes:

“Byzantine Thessaloniki flourished in spite of wars in the region. Its population exceeded 100,000 inhabitants in the middle of the 12th century.”

Stefanos continues by listing looting, massacres, enslavement, and deportations that occurred in 1430 when the Ottoman Turks occupied Thessalonica, resulting in a mass exodus and desertion of the city.

The city's population fled deeper into Macedonia, and there appear to be a number of families and groups of people there today who trace their history to the devastation of Thessalonica. As elsewhere in the Balkans, the national identities of certain populations is largely based on the shift of power from the Byzantine Empire to the Ottoman Empire, who ruled the Balkans afterward for five hundred years.

Lord (2000), in his The Singer of Tales, a seminal research on epic oral singing carried out in1933-35 in the Balkans, reminds us indirectly of a relationship of heroic song to national identities—from as far back as Homer's characters to insurgent heroes of Ottoman Empire. Most of the heroic oral songs mirror the profound articulations of St?nil? (2006) in The Myth Of The Rebel Hero: Identity Issues In The Balkans:

The courage and exemplarity of otherwise marginal heroes stand for their irrepressible desire to experience the center, under the guise of a permanent revolt that gave birth to the prototype of the rebel hero.

All of this identity strife, particularly since 19th century western European interest in Mediterranean hegemony, paints the Ottoman Empire as unsophisticated and brutal, in a way very similar to the portrayal and memory of Arab Spain after the re-conquest. Like any other large society, the Ottoman Empire was a complex intercultural system, where violence was counterbalanced by the amenities of urban life and the patronage of the arts and sciences, along with a certain level of inter-religious coexistence.

But the wound would not heal, and Thessalonica declined for almost sixty years after the Ottoman conquest of 1430. The next sultan, Bayezid II, invited a whole new group of people to settle in Thessalonica—Jewish refugees from Spain—who brought prosperity to the city for the next four hundred years.

Ojalvo (2005) in the commemorative book of the Quincentennial Foundation of Istanbul, writes of the pressure the Catholic church placed on Ferdinand and Isabella, forcing them in 1492 to sign the Alhambra Decree, which expelled the Jews from Spain. Ojalvo continues:

The last lot of Jews gathered in the port of Cadiz faced a dilemma: Those who left port were attacked by the pirates, those who went on land were burned at the stake by the inquisition. About a thousand people waited in anguish. At the last minute arrived a small fleet manned by the Turkish admiral Kemal Reis, who took the refugees under his protection, thus organizing a convoy of Jewish immigrants towards the Ottoman empire.

Musicologists and eminent practitioners of early Spanish music, such as Jordi Savall, have traveled to Izmir, Sarajevo, Fez, and Thessalonica, seeking songs from the once rich Arab-Andalusian music tradition of the Iberian Peninsula (La Lira d'Esperia, CD.1995)

So we could summarize with the thought that nearly anywhere where there are crowds of refugees, long lines of deportees and stranded migrants, there is, over and over again, someone—often an anonymous musician, with or without an instrument—beguiling the crowd. In the theater piece Tarantella, Tarantula (Paich, 2006), about Italian immigration to America at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the main character is one such anonymous musician. The narrator describes her like this:

On the ship, Giovannina assisted passengers who were seasick. She also helped clean the steerage quarters from vomit and the mess left after meals. There were so many rats on board. Giovannina also lifted their spirits by singing familiar songs as she did back home in the village square. She had a special gift: not only to understand the needs of the individuals, but she could read and console a familiar crowd with the right song for the moment.

Conclusion

Two days ago, [17 August 2007] Spanish mountaineers met a 27-year old immigrant from Mali at an altitude of 3,392 m in the Spanish Sierra Nevada, near Granada, Andalucía. When they reported the young man to the police, he had already climbed up to 3,428 m before he was found and arrested by the Spanish Guardia Civil. He had no food or water provisions with him. He stands a good chance of being deported, back to Africa (Pearson, 2007).

This piece of contemporary news about the unbelievable individual achievement of an informal representative of his people, an inadvertent explorer and survivor, may help us imagine the achievements of itinerant musicians, as well as other travelers and explorers throughout Mediterranean history.

The Umayyad prince Abd al-Rahman I, the Falcon of Andaluse (731-788), was the only survivor of the royal massacre in Damascus. He escaped and traveled for four years until he reached his relatives in Morocco and Spain. There, he claimed his domain and fathered one of the most advanced cultures in the Mediterranean basin at that time.

It may have bean equally unbelievable to see a traveler from Constantinople, with a small kamase, a predecessor of the violin, playing in the evening at some roadside in Provance, far away from his intended destination, in search of an aristocratic patron, hoping to be invited to someone's home. Or equally disconcerting: the presence of a European Troubadour, such as St. Francis, singing at the gates of Damascus until he sings the sultan's or guards' favorite song, and is received. Perhaps he learned it on his travels through Spain a few years earlier.

Now let us look at the transmigration of music from another angle. The album from Tekameli, Chants Religieux Gitans, is a recording of the contemporary religious singing of Roma People [Gypsies] from Perpignan in the south of France. The insert's text describes their relationship to the language they sing in:

The usual language of the Gitans of Perpignan is Catalan. Spanish is usually the language reserved for music (French is used to communicate to 'payos' [non Gypsies] who do not speak Catalan). The members of the Espinas—Cargol family [Tekameli], following the Gitan tradition, use Spanish to sing, yet Spanish is almost a foreign language to them (Escudero, Bertrand, Moreno & Beattie G. 2008).

This contemporary example, from the same general geography of the Troubadours, is an illustration of the migration of music, ideas, and linguistic conventions. It is reminiscent of Alfonso X, proclaiming Galician, a close relative of Occitan, 'a language of poetry.' In the same way, Spanish, in the case of the contemporary Roma singers in France, has become the lingua franca of art and devotion. The music of Tekameli combines Arab-Andaluse devotional inflections, which survive in Flamenco with Catalan Rumba and Cuban Salsa, and folds these modalities into the religious songs of French Gypsies who sing in Spanish. Their passionate, sensuous music is a living example of transmigration and the adaptability of music as a cultural phenomenon.

The paradox of sensuality in some religious devotional songs to the saints—in particular Mary—and the de-materialization and idealization of love songs directed towards a real or imaginary lover is a central pivot for reflecting upon the role of itinerant musicians in Mediterranean cultures and culture in general. The musicians can be described almost as messengers of fecundity and as carriers of solace for the yearning and brooding of human complexities.

C. G. Jung, who was both a medical doctor and a psychologist, explored these same tensions of concrete, manifested, and sublimated expression when describing the work of the itinerant medic, the father of modern medicine, Paracelsus:

Paracelsus carefully avoids the ecclesiastical terminology and uses instead an esoteric language, which is extremely difficult to decipher, for the obvious purpose of segregating the 'natural' transformation mystery from the religious one and effectively concealing it from prying eyes (Jung, 1983).

Jung continues to reflect on how Paracelsus' work was in some way opposed to the established religious understanding of mystery, because the ambiguities of Eros were also included in it. In the same paragraph he continues:

…a more cogent motive was his experience as a physician who had to deal with man as he is and not as he should be, and biologically speaking, never can be. Many questions are put to a doctor which he cannot honestly answer with ‘should’ but only from his knowledge and experience of nature (Jung, 1983).

The lyrics of the Troubadours and Trouveres may, in the same way, carry messages from the authors' deeply sensual, or conventionally religious personal experiences. Their aesthetic grew beyond both the vernacular love song and the devotional ecclesiastic one, and pointed in both directions: from vernacular to sacred, and from sublimated to real.

Our final example may plunge us into some of the complexities we have touched upon before and help us make some concluding open-ended observations.

Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, in the south of France, is situated at the estuary where the Rhone meets the Mediterranean. The town is like a miniature medieval sister, perhaps a port of call for ships from Alexandria or Tyre, or a smugglers' enclave, on the other side of the Mediterranean world.

The town, with its fortified Romanesque church, is home to three sculptures depicting political refugees of high rank: survivors of an expulsion and a perilous journey. After the crucifixion of Christ and disappearance of his body from the tomb, it is believed—particularly by the Roma people—that Mary Magdalene, Marie-Salome, Marie-Jacobe, Lazarus, and several other disciples were forced, in 45 AD, to flee Palestine by boat, crossing the Mediterranean Sea.

They landed near the present-day village of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer (Marre, 1992). Marie-Salome and Marie-Jacobe, became, in time, worshiped by the local people and pilgrims, while Mary Magdalene was celebrated in the environs of Marseille. But in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer there is a third sculpture, of Sara-la-Kali, venerated by the gypsy pilgrims every year.

Not much is known about the black Egyptian woman represented by the sculpture. Each year on May 24 and 25, the three statues of the women, those strangers from far across the sea, become the destination of the 'Pilgrimage of the Gypsies' (Marre, 1992). Marre, describes the ceremony:

As a dozen nationalities from all over Europe accompanied the service with music and song, an ornately painted box was lowered from the church roof, containing the remnants of Saint Sarah, gypsy patron saint of travel. To gypsies, she is known as Sara the Egyptian, because they believe she traveled here from Egypt. A huge queue formed to touch and kiss the face of the black Madonna. As the box was slowly lowered by ropes in the congregation, their hands reached up above the flickering candles to touch and be blessed by her presence. In Romany, her name is not, in fact, Sara the Egyptian but Black One or Kali. Kali is the name of the Indian Goddess of time [sic] (Marre, 1992).

In the continuum from goddess to real woman and back, the adoration and act of being adored is probably an important part of culture making, a motivator. Maybe our collective poetic, symbolizing capacities are ignited by, and make elaborations for, Eros's sake. The enduring need for, and power of, music and sung poetry energizes the fertility of both imagination and biology. Fashion is an example of poetic elaborations for Eros's sake. The symbol and sign-making faculty of humans is, possibly, a response to a primal need for the creation of a shared, tangible—but also intangible—space of cultural experience.

William Hans Mille, the author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language and the Brain, reviews the work of the UCLA neuro-anatomist and psychologist Harry Jerison, where he writes:

The more we understand about the nature and origin of our symbolic capacities, he claims, the better we can regulate our enormous cognitive potential. He [Jerison] wrote his ‘mystery novel,’ as he calls it, with this goal of increasing our understanding about how symbol reference and language came about, and ultimately, of who we are (Mille, 1997).

The Troubadour paradox of singing both to a symbolic and to a real lady is, possibly, a glimpse and approach toward understanding the essential human desire for continuity. This desire is not only for the continuity of biology, progeny, and the species, but is also a desire for the continuity of the elusive cognitive and symbolizing elements—the very elements that characterize the existence of language and consciousness.

This needs for continuity of all the aspects of human existence—the body and the yearning soul—manifest as culture. In return, the culture contains aspirations, drives, and the finest expressions. The fin d'amour of the Troubadours is an example. In spite of, and in contrast to, an atmosphere of continuous strife and war, this process of culture-continuing allows for a development of ideas within some kind of agreed upon stability—even if that stability lasts only for a generation, or manifests in a single geographic area.

Significant aspects of this process are the songs and dances, and their continuity through the transmigration of music—from musician to musician, place to place, from one century to the next. And in the end, everyone in the world, professional or lay, has a favorite song—and some can even sing it. The Mediterranean has been an intriguing and fascinating field for all of these confluences to mutate, mature, contradict, flourish, and continue.

Bibliography

Arberry A.J.(trans.) (1953). Ibn Hazm (994-1064) Tawq al-hamama: The ring of the dove: a treatise on the art and practice of Arab love, xii. London: Luzac & Company.

Bogin M. (1980). The Women Troubadours. New York: W.W. Norton &

Company.Clifton C.S. (1998). Encyclopedia of heresies and heretics, 121. New York: Barnes & Noble.

Dzielska M. (2002). Hypatia of Alexandria. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Escudero J.P., Bertrand G., Moreno A.M., Beattie G. (2008). Tecameli: Chants religieux Gitan, compact disc insert. Montreuil: Longdistance & Harmonia Mundi.

Goldberg contributor (2003) ‘Giovanni Battista Pergolesi.’ Goldberg Web Magazine, Composer biographies. Available at: http://www.goldbergweb.com/en/history/composers/11747.php [8 January 2008].

Jung C.G. (1983). Alchemical studies, 157. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Leaman O. & Albdour S. (1998). Ibn Hazm, Abu Muhammad 'Ali (994-1063) New York: Routledge.

Levitin D.J. (2006). This is your brain on music, 197. New York: Plume.

Lewis C.S. (2007) The discarded image: an introduction to medieval and renaissance literature. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lord A.B. (2000). The singer of tales. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lunde P. (2005) 'Monsoons, mude and gold.' Saudi Aramco World 56(4): 4-11.

MacLennan B. (2001). 'An interpretation of courtly love.' University of Tennessee class notes. Available at:http://www.cs.utk.edu/~mclennan/Classes/US310/Interp-Court-Love.html [15 January 2008].

Markale J. (2007) Eleanor of Aquitane: queen of the troubadours. Rochester: Inner Traditions.

Marre J. (1992). The romany trail, part 1: Gypsy music into Africa. London: BBC documentary.

Menocal M.R. (2002) Ornament of the world, 220-222. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Ojalvo H. (1999) Ottoman sultans and their Jewish subjects. Istanbul: Quincentennial Foundation.

Pearson C. (2007). 'Ceuta and Melilla: two Spaniards in Africa.' Mallorca: theARXXIDUC: news from Mallorca, Spain, the Mediterranean, Europe and the World. Available at: http://arxxiduc.wordpress.com/category/immigration/ [5 February 2008].

Pearson C. (2007). ‘Dramatic increase in illegal immigrants to Spain.’ Mallorca: theARXXIDUC: news from Mallorca, Spain, the Mediterranean, Europe and the World. Available at: http://arxxiduc.wordpress.com/2007/09/04/397/ [5 February 2008].

Petersen S.H. (2006) 'A list of the works commissioned by Alfonso X, el Sabio.' University of Washington faculty page. Available at: http://faculty.washington.edu/petersen/alfonso/alfworks.htm#poetry [10 January 2008].

Schama S. (1995) Landscape and memory. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Shackleton N. & Renfrew C. (1970). ‘Neolithic trade routes re-aligned by oxygen isotope analyses.’ Nature 288: 1062 — 1065.

Stefanos S. (2004) ‘Thessaloniki,’ Virtual Tourist Travel Guide. Available at: http://members.virtualtourist.com/m/22b26/65cb4/ [1 February 2008].

Tyerman C. (2006). God's war: a new history of the crusades. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Yates F.A. (1984) The art of memory. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Selected Discography

Alfonso X El Sabio Cantigas de Santa Maria, Joel Cohen with the Abdelkrim Rais Andalusian Orchestra of Fes conducted by Mohammed Briouel. Erato Disqes S.A., 1999. [3984-25498-2]

Alfonso X "El Sabio" Cantigas de Santa Maria, Ensemble Unicorn, Vienna. HNH International Ltd., 1995. [8.553133]

Ballads of the Sephardic Jews, Sarband. Dorian Recordings, 1994. Compact disc. [DOR-93190]

Black Madonna, The — Pilgrims Songs from the Monastery of Montserrat (1400-1420), Ensemble Unicorn conducted by Michael Posch. HNH International, 1998, distributed by Naxos. [8.554256]

Cantigas de Santa Maria, Ensemble Gilles Binchois. Sound Arts AG, 2005. [AMB 9973]

Cantigas of Santa Maria of Alfonso X, The Martin Best Ensemble. Nimbus Records, 1984. Compact disc. [NI 5081]

Esma, The Queen of the Gypsies, My Story, Esma redzepova & Ansambl Teodosievski with Titi Robin. Accords Croisés, 2007. [AC119]

From Byzantium to Andalusia — Medieval Music and Poetry, Oni Wytars Ensemble - Peter Ravanser, Belinda Sykes and Jeremy Avis. Naxos Rights International Ltd., 2006. Compact disc. [8.557637]

Iberian Garden Volume I, Altamar Medieval Music Ensemble. Dorian Discovery, 1995. Compact disc. [DIS-80151]

Music for Alfonso the Wise, The Dufay Collective. Harmonia mundi usa, 2005. [HMU 907390]

Spanish Music of Travel and Discovery, The Waverly Consort conducted by Michael Jaffee. Angel Records, 1992. [7243-5-61815-2-6]

Marions les Roses — chansons & psaumes, de la France à l'Empire Ottoman, Les Fin'Amoureuses. Alpha Production, 2005. [517]

Terra Nostra, Savina Yannatou & Primavera en Salonico. ECM Records, 2003. [440067172-2]

The Pilgrimage to Santiago, The New London Consort directed by Philip Pickett. The Decca Record Company Limited, 1991. [433 148-2]

Marcel Cellier presents Mysterious Albania. ARC Music Productions International Ltd., 2002. [EUCD 1762&93;

ALBANIE Pays labë, Plaintes et chants d'amour. Ocora Radio France, 2003. [C560188/HM76]

Le Chant des Troubadours vol. 2, Les Troubadours du Périgord, Ensemble Tre Fontane. Alba musica, 1993.

Corsica/Corse: Rusiu — Religious Music of Oral Tradition. Auvidis-Unesco, 1989. [D8012]

The World of Early Music — From the Middle Ages to the Dawn of the Enlightenment. Naxos. [DDD 8.554770-71]

Tenore de Orosei — amore profundhu, Viches de Sardinna [1].Winter & Winter, 1998. [910 021-2]

Troubadours, Trouvères & Minnesänger. Harmonia mundi, 2005. [HMX2908166]